Thanks to my tireless work complaining about some of the least important things happening in the world today, and concocting brilliant solutions for all of them, video games are now pretty much perfect. But when I first began writing these articles more than a year ago, the industry was a total mess, a real jamboree of broken nonsense. Unfixed problems had been allowed to percolate for decades, like a turd in a French press.

For example, remember how, back in 2004, every game would feature an NPC called Bad Darren who would follow you around making all of the weapon sounds? It wasn’t until I published my Pulitzer-nominated article The Problem With Bad Darren that these so-called game designers finally took notice of their tired-ass trope, deleted Darren from their games and made the sound files come out of the guns instead.

But a fixer’s work is never done, and the well of clichés has not yet run dry. Inspiration for this month’s fix comes in the form of the big news of the hour: those evil Russian hackers and all of their election meddling. Hacking is as commonplace a trope in gaming as any Bad Darren or Tiny Susan (the woman who would follow you around holding all your gems) ever was, but like the sore arse you’re too embarrassed to go to your GP about, the problem persists.

The Problem

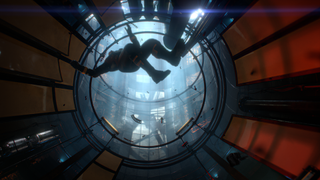

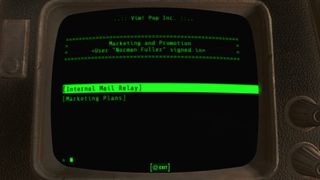

Released barely days ago, Prey has you guiding a ball bearing into a hole to unlock doors and hack turrets, as though you were a bored CEO fidgeting with a desk toy. The Fallout games have you guessing passwords like a suspicious housewife. And the worst offender of the lot, BioShock, seems to have confused hacking with plumbing-in an en suite.

Real-world hacking is vastly more complex (and infinitely more boring) than the kind of hacking depicted in cinema and gaming. It involves something called TCP/IP and zero-day exploits, and rather than opening a weapons locker in another room it instead results in a ranting misogynist becoming the most powerful man on the planet, or a cache of celebrity foofs appearing on Reddit.

It’s impossible to recreate hacking in a game with any real fidelity, so instead designers create metaphorical minigames for us. A ball and a hole become a ‘data packet’ and a ‘server node’. An enemy chasing you around a grid is now a ‘virus’ propagating through an ‘intranet’.

You can make your own hacking minigame next time you’re out shopping. Simply pick any Fisher Price toy off the shelf and relabel all of the primary coloured buttons, wheels and whistles as ‘trojans’, ‘remote uplinks’ and ‘mainframes’. Hey presto, you’re halfway to creating the new Deus Ex.

The Solution

It’s time we made hacking minigames more believable, but how? Well, while it will never be feasible to fully emulate the specifics of hacking, we can still recreate the real-world stakes involved. So each time you fail to properly hack a keypad, rewire a camera or decode a robotic bird in a game, there is a four percent chance that an international warrant will be issued for your arrest.

You can choose to claim asylum inside the Ecuadorian embassy should you wish to avoid facing the charges made against you, but know that doing so will reduce your hacking ability in games by seven points, and substantially increase your notoriety. Also, I hear that the internet connection in there is properly shoddy, so Xbox Live is pretty much off the table.

When the punishment is this realistic, you’ll be far too terrified of the consequences of bumping your ‘data packet’ into the wrong ‘server node’ to care that you’ve played the same minigame thousands of times. And that, no matter what anybody else might say, counts as a solution.